The second black player to represent England at any level and the first British player to transfer to Real Madrid, Laurie Cunningham was a footballing pioneer and a legend of his own time. His premature death at 33 years of age cut short the career of a player who “was as good as Cristiano Ronaldo” according to Spanish manager, and former Real teammate, Vincente del Bosque.

Born on March 8, 1956 in Archway, London, Laurie Cunningham was the son of a former Jamaican jockey and raised in one of the poorest districts in London. As a 16-year-old, Laurie was turned down by Arsenal before joining Leyton Orient in 1974.

Orient were then in England’s Second Division, two years removed from their famous comeback victory over Chelsea in the FA Cup 5th round. Laurie, a relative unknown talent at the time, signed for Orient on a Monday. On Tuesday, designated as his first scheduled training session with the team, he failed to show up. On Wednesday, Orient sent an employee to his house to check up on him, only to find their new signing sound asleep in bed.

Never one to appear flustered or rushed, he showed up to training and casually strolled across the pitch, the Orient manager immediately pinning his new signing as either a lunatic or a very special individual.

Orient threatened Laurie with a fine of £1 for his truancy, a fine which would be doubled for every subsequent tardy he accumulated. Laurie, an accomplished dancer who’d been offered a part in a ballet company, would use the money he accumulated from dance competitions to pay these fines.

Laurie’s interest in dance, ballet, reggae, funk and soul music was evident in his playing style. A mixture of pace, grace and control, Laurie Cunningham was dynamic and explosive with the ball at his feet. His ability to stop and turn quickly saw him frequently beat two or three defenders with immaculate ease.

“Suppleness?” replied Laurie to one reporter's line of questioning, “That comes with dancing. I love soul music.”

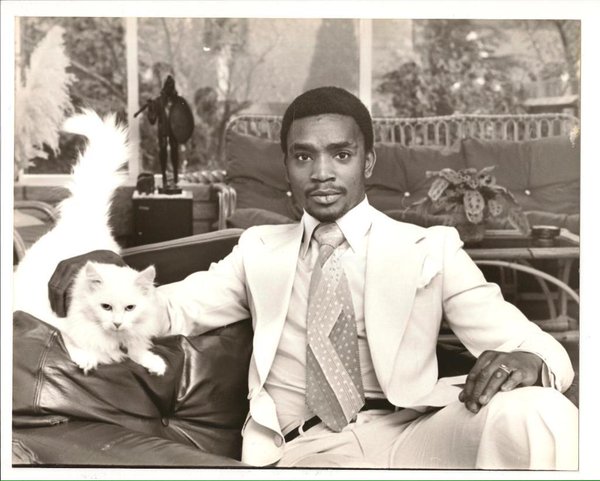

He also loved leather trousers, fur coats, fedoras, and had a fondness for etiquette, good wine and king prawns. The varied and brash interests of Laurie were aligned with the quiet personal demeanor of a self described “dreamer”. His main outlet of expression came through his football. More often than not, he let his feet do the talking.

While superb performances for Orient immediately established him as a special player, his career would long be spent battling the labels and categorizations that came with the color of his skin and his unique individuality.

Laurie transferred to West Bromwich Albion in 1977 for £100,000, where his performances would catch the eye of both the English National Team and continental Europe. Under Ron Atkinson, West Brom simultaneously fielded three black players for only the second time in the history of the English top flight. Their attractive, attacking style of play quickly made them the neutral fan's favorite.

Laurie Cunningham, Brendon Batson and Cyrille Regis were affectionately referred to as “The Three Degrees”, after the U.S. soul singing trio of the same moniker. However, the reception they received outside of West Brom was generally anything but affectionate.

England in the 1970s had seen a rise in both the National Front and the British Movement, extreme right-wing groups which subjected black players to monkey chants, boos, bananas and letters in the post which were full of hate speech, threats and swastikas. Overt racism was rife within English stadiums and Laurie’s style of play made him a constant target.

Herman Ouseley, a British parliamentarian and the Chairperson of Kick It Out, vividly recalls a match he attended between West Brom and Chelsea where “the booing was incessant, because the three black players were touching the ball a lot. Twenty minutes into the game, Laurie Cunningham got the ball, skated through the Chelsea defence, banged it in the back of the net and they got even worse.

"Twenty minutes later," Ouseley continued, "Laurie Cunningham picked the ball up, zoomed through their defence and banged it in the net again. I'm in with the Chelsea fans and everybody's booing, and one of the big guys in front of me turns to the other and says, 'Mind you, the nigger is fucking good, isn't he?' That gave me a lift, because what it said to me was that these guys hated black people and wanted to destroy them, but at least the skill of a black player had risen above that.”

In another match against Millwall, reporter Jeff Powell noted that, “a large section of Millwall’s visiting supporters began jumping on the spot, flapping their arms and chanting ‘coon, coon, coon" whenever Laurie touched the ball.

Laurie finished the match with a superb solo run in the game’s final moments, finishing in the top right corner before celebrating in front of the Millwall supporters with a raised fist of strength and defiance.

“I’m the natural target, but I don’t let it get to me,” said Laurie, “I’d be doing what they want. There’s no way I’d ever be ashamed of being black but it’s more important that other professionals seem to have stopped calling me things.”

Laurie’s performances saw him become the second black player to wear an England shirt at any level. He marked his debut with a milestone winner for England’s under-21s against Scotland. He would go on to earn his first full England cap against Wales in 1979.

Laurie’s display against Manchester United, a 5-3 victory for West Brom during which he tormented the Red Devil’s fullbacks, lead the commentator to remark “the magic that black footballers are brining to the league is completely on evidence” at full-time.

The first name on the team sheet, Laurie scored 21 goals in three seasons for West Brom, helping the side reach the semi-finals of the FA Cup and qualifying for Europe. It was his performance against Valencia in the UEFA Cup which captured the attention of Real Madrid.

At the time, Real Madrid was only allowed two foreign players in their squad, so their valuation of Laurie’s talent was undeniable.

“Madrid viewed him as one of the most distinguished footballers in Europe,” said del Bosque. “It was a period when there weren’t many international signings and the club made a special effort financially to sign Laurie, to sign a star, because almost all the rest of us were from the youth team.”

In 1979, he became the first British player in modern history to arrive at the Bernabéu.

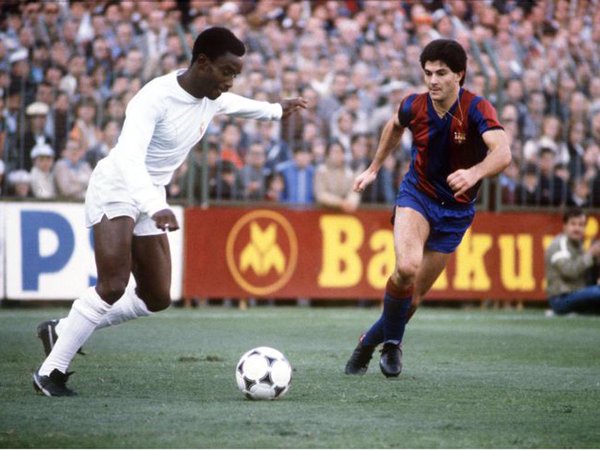

Laurie blossomed in his first season at Real Madrid, coming alive everytime the ball was at his feet and dazzling supporters. Nicknamed “The Black Pearl” and “El Negro de Los Blancos”, Laurie quickly became the star attraction of a phenomenal Real Madrid side.

On February 10, 1980, Laurie received a standing ovation from Nou Camp supporters for his imperious display in a 2-0 Real victory. He’s the last Real Madrid player to receive such an honor from Barcelona supporters. Madrid newspaper AS ran a 25th anniversary feature of the game with the headline, “The Man Who Ran Riot in the Nou Camp”.

Laurie scored eight goals in 29 La Liga appearances in his debut season. Real Madrid would go on to win La Liga and the Copa del Rey, narrowly missing out on the treble after losing to Hamburg in the European Cup semi-finals, which Laurie scored in.

A crowd favorite who played with a flamboyance rarely seen during that time period, Laurie frequently took corners with the outside of his foot to produce an extraordinary curve, his step overs, flicks and tricks weren’t as well appreciated by the national team. After his successful season with Real Madrid, Laurie was preposterously omitted from the England side at EURO 1980, a tournament which saw England crash out at the group stage.

Laurie would collect his sixth and final cap against Romania in a 1982 World Cup Qualifier. For a player so talented, it's a remarkably dissapointing total.

Laurie’s next three seasons at Real were marked by a succession of injuries and bad press. He played the whole match against Liverpool in the 1981 European Cup Final, a match which Madrid lost 1-0, but was unable to recapture the form of his first season.

Operation on a broken toe, a serious thigh injury, three surgeries on his left knee, all of which didn’t go well, took a toll on Laurie both psychologically and physically.

Laurie was also photographed in nightclubs during his time out, hardly surprising for an individual so fond of dancing, but the Spanish press billed him as a playboy, as a big money signing who was more interested in music and fashion rather than representing Real Madrid.

Laurie's relationship with his white girlfriend Nicky Brown, they'd been in a long-term relationship since they were teenagers, was also the source of negative public discourse.

They were unmarried but controversially lived together in a largely Catholic Spain. Nicky was the only one able to provide a genuine level of trust and care during the beginning of his time in Madrid - agents and travelling entourages having not yet been realized. Nicky was his one point of stability, but their relationship soon deteriorated. Laurie lost his way.

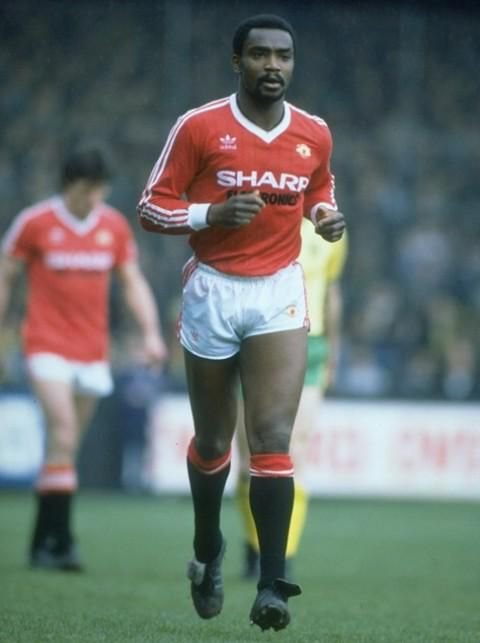

With Real Madrid looking to allocate their two foreign player slots on new talent, Laurie joined Sporting Gijón after a failed loan to Manchester United.

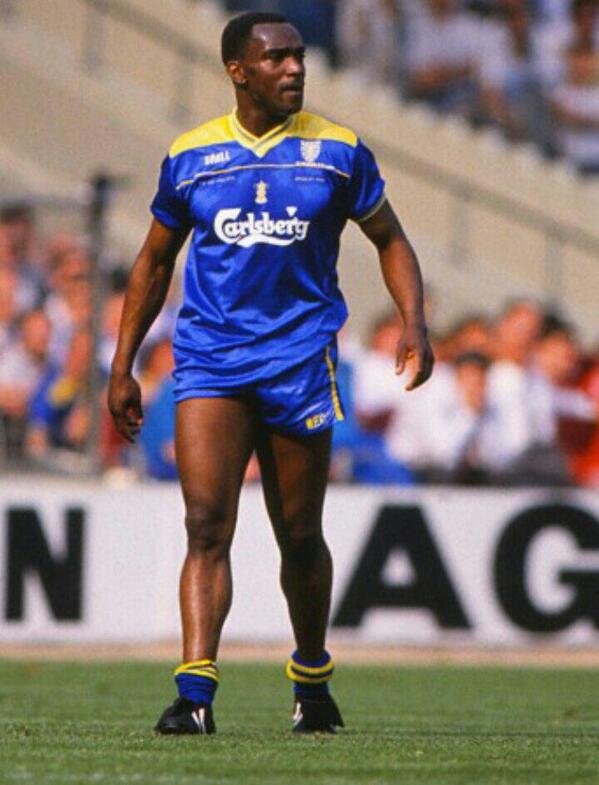

The next six years would see Laurie appear for Gijón in Spain, Marseille in France, Leicester City in England, Rayo Vallecano in Spain, Charleroi in Belgium and Wimbledon in England.

He married Sylvia Sendin-Soria, who revealed that “there were days when you saw him low. When a man has been so high and then has to settle for less it shows.” With injuries taking their toll and Laurie starting to realize the fleeting nature of his career, it seemed as though he'd fallen off the map completely.

In the end, Laurie just wanted to play. His stint with Wimbledon in 1988, a team notorious for their rough play and heavy tackling, was a surreal moment for most English football fans. Appearing in only 6 First Division games, Laurie appeared as a substitute in their FA Cup final upset of Liverpool.

A scene from “First Among Equals: The Laurie Cunningham Story” shows a clip from the London Minority Unit Documentary, a unit established by ITV in the 1980s to produce programming aimed at black, Asian and other minority audiences.

In the clip, esteemed Sunday Times sports writer Rob Hughes discusses the prejudices against black footballers as revealed by a survey of English managers. “When we asked the 14 managers, who were in the First and Second divisions at the time, whether they would be prepared to include a black player in their side,” says Hughes,”almost to a man, the reason was, in the managerial jargon, that ‘black players lack bottle’.”

Black players were stereotyped as being soft, unfit for the conditions of top level football.

Later, the documentary shows a revealing interview between Laurie and a British reporter sent to interview him in Madrid. After his initial success in the Spanish capital, Laurie’s time in Madrid had been beset by injuries and the reporter asks to see the extent of the damage.

Rolling up his pant leg, Laurie reveals a long scar running down the length of his inner left knee. The scar is the result of surgery on a ruptured knee ligament, incurred through a horrific tackle from a Madrid teammate during training.

The broadcaster notices the bumps, scars and cuts located around the surgical scar and asks what those are from. “When players see the scar...,” replies an impassive Laurie, “the reactions of the players after I got the injury and I started playing again. They’d look at the leg and see the scar and come into me. Everyone is trying to trample me out again.”

Nearly ten years after the surgeries, Laurie Cunningham was still taking players on, regardless of the kicks and abuse he received.

When confronted with the stereotypes surrounding black players, Laurie responded, “How come black skin lacks courage when Muhammad Ali is champion of the world?”

The 1988/99 season saw Laurie help Rayo Vallecano achieve promotion to La Liga, his goal securing promotion for the club. Watching a Real Madrid match with a friend, Laurie told him, “Next year, I’ll come back and show them what they missed.”

On July 15, 1989, weeks away from returning to the Spanish top flight with Rayo Vallecano, Laurie Cunningham was killed when he swerved to avoid a car with a flat tire and was thrown from the vehicle. One of the world's truly exceptional trailblazers had been lost at only 33 years of age.

One of England’s unsung heroes, Laurie Cunningham demolished the stereotypes surrounding black footballers while refusing to be anyone but himself. The introverted extrovert, Laurie exuded class, style and panache.

You can watch "First Among Equals: The Laurie Cunningham Story" in its entirety here.